They successfully presented their research at the New England Regional Conference of the World History Association.

If you see them in the corridors, ask them about their research!

Annie Costello presented a paper titled: “Who is building the ship? The Thematic Plan to introduce Soviet women to the workforce through art”

Kenneth Laurent presented a paper titled: “Trujillo El Marino: The US Marines role in the rise of Rafael Trujillo”

Caroline Tempesta presented a paper titled: “The St. Louis: Immigration Policy as Life or Death”

REMEMBERING WOMEN HISTORY

Dr. Rebecca Crumpler was the first female African-American doctor of medicine in the United States. Born in 1831, Rebecca was raised by her aunt in Pennsylvania, who acted as the community doctor, and moved to Charlestown, Massachusetts in 1852. Rebecca worked as a nurse from 1855 to 1864, and was admitted to the New England Female Medical College in 1860. Her husband, the former enslaved Wyatt Lee, passed away from TB in 1863. In 1864, she became a doctor and practiced primarily for Boston’s poor African-American women and children.

Rebecca married her second husband, Arthur Crumpler, a former fugitive enslaved man in 1864 or 1865. At the end of the Civil War, they moved to Virginia and Rebecca worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau to care for the enslaved who had been freed. Racism was rampant, and they moved back to Boston; Joy Street in Beacon Hill, when it was primarily an African-American neighborhood. Rebecca taught, gave birth to Lizzie in 1870, attended the elite West-Newton English and Classical School, and also wrote A Book of Medical Discourses in 1888. The Crumplers moved to Hyde Park in the 1880s.

Rebecca Crumpler died on March 9, 1895, and unfortunately there are no surviving pictures, paintings or drawings of her. She and Arthur are buried in Fairview Cemetery. Their former home on Joy Street is part of Boston’s Black Heritage Trail, and the Women’s History Trail. One of the first medical societies for African-American women, is named in Rebecca’s honor. Dr. Rebecca Cole, another female African-American first in her own right, is often confused with Dr. Rebecca Crumpler. Dr. Crumpler received her degree 3 years earlier than Dr. Cole.

Friends of the Hyde Park Library have started the Crumpler Fund to raise money to provide Rebecca and Arthur with proper gravestones in Fairview Cemetery. Donation info is here.

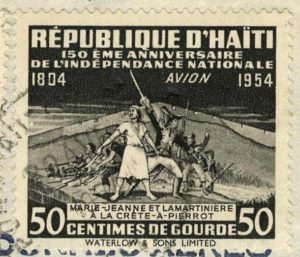

Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniére, often known only as Marie-Jeanne, was one of a few women who served in the Haitian army during the Haitian Revolution. Unfortunately, not much is known about her early life. Dressed in a man’s uniform, she fought alongside her husband, Louis Daure Lamartiniére at the Battle of Crête-à-Pierrot in 1802. She fought courageously which helped to boost morale, and she also nursed her wounded comrades. Her husband was killed during an ambush later in 1802.

Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniére’s life after independence from France is mostly unknown, though there are a few stories. Two other known female revolution fighters to check out are Abdaraya Toya aka Victoria Montou, and Sanité Bélair.

Ada Blackjack, an Inupiaq woman, lived as a castaway on the uninhabited Wrangel Island, north of Siberia for a few years due to a disastrous expedition. Born in Alaska in 1898, she was raised by missionaries who taught her English and domestic skills. Later in life, struggling as a single mother to a sick child, she placed him in an orphanage until she could provide for him. In 1921, she saw the opportunity, and joined the Wrangel Island Expedition, funded by Vilhjalmur Stefansson. His reasonings for the expedition are a little sketchy; maybe a little self-promotion, and/ or trying to make up for Karluk disaster, but either way, mistakes and bad choices were made.

Ada was misled to think that the expedition would be made up of more Alaskan Natives. The rest of the team of men included one American and three Canadians who were inexperienced with Arctic exploration. Ada was hired as the cook and seamstress. The team was to be relieved by a new one in 1922, but the ship never showed up.

In January of 1923, conditions turned disastrous; rations ran out, and three team members left to find help and food. Ada was left with Victoria the cat, and Lorne Knight who had scurvy,. She nursed him even though he was verbally and mentally abusive towards her. Lorne died in June, and the other three men never returned.Ada knew no survival skills. On her own, she learned how to shoot and trap foxes. She hauled driftwood and chopped it for fire. Ada built two lightweight boats out of driftwood, canvas, and animal skin so she could hunt more successfully.

Ada Blackjack and Victoria were rescued in August of 1923, by Harold Noice. They had been on the island for almost 2 years. Ada didn’t profit from any of fanfare over the expedition, was able to get her son back, gave birth to another son, didn’t give interviews until she was much older, and struggled with poverty for the rest of her life. Ada died in Anchorage in 1983, at 85.

Pōmare IV, born ʻAimata Pōmare IV Vahine-o-Punuateraʻitua in 1813, was the Queen of Tahiti from 1827 to 1877. She was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Tahiti. In 1843, France declared Tahiti a French protectorate and installed a governor. Pomare tried to stop further French intervention by writing to the King, Louis Philippe I, and asked Queen Victoria for help. In protest, Pōmare exiled herself to Raiatea. The French-Tahitian War took place from 1843-1847, and involved all of the Society Islands. The French won, but because of pressure from England, they were unable to take over Tahiti, so the island and Moorea were ruled under the French protectorate. A clause in the war settlement stated that Queen Pōmare’s allies, Bora Bora, Raiatea and Huahine remain independent.

Queen Pōmare IV ruled under French administration from 1847-1877. She placed some of her 10 children in positions of power in Tahiti and the Leeward Islands, including her daughter Teri’i-maeva-rua I, who became Queen of Bora Bora. She died in 1877 and was succeeded by her son.

Jane Bolin was a woman of firsts. She is mainly known as the first African American female judge in the US. Born in 1908, her lawyer father Gaius was also a man of firsts, including the first black graduate of Williams College. Due to racism, Jane and the only other black student in her freshman class moved off of Wellesley College’s campus, but she graduated in 1928 as a “Wellesley Scholar.” She was the first African American to earn a law degree at Yale, as well as the first African American woman to join the NYC bar association, and the first African American female lawyer hired by the NYC Law Department. She was sworn in as a family court judge in 1939 by Mayor La Guardia. Jane promoted the requirement of child care agencies that receive public funding, to accept children regardless of their race or ethnicity, and ended the practice of assigning probation officers based on race or religion.

Jane Bolin was reappointed to her seat by three more mayors, for three more 10 year terms. She retired when she hit the mandatory retirement age of 70, and she continued to advocate for children’s rights and education. Jane died in 2007 at the age of 98.

Ga’axstal’as, also known as Jane Constance Cook, was a First Nations leader and activist of the Kwakwaka’wakw people. Born in 1870 on Canada’s Vancouver Island to a noblewoman and a white fur trader, Jane was raised by missionaries, and trained as a midwife and healer. She was bilingual, and had a good understanding of colonial legal and government systems. Jane fought for land and resource rights for her people, and advocated for women and children. In 1914, she testified at the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission, and was the only woman to serve on the executive of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia.

Jane Constance Cook raised 16 children, and died in 1953.

Written by Jaclyn Foster

Jackie graduated from Emmanuel in 2006 with a BA in history and secondary education. She has a masters degree from Boston College. She is currently the Manager, Program Operations at Facing History and Ourselves.